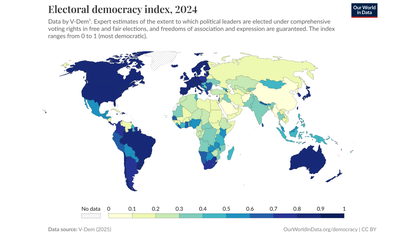

Democracy as a form of government that stands for free elections, separation of powers, the rule of law, freedom of expression, and the protection of human rights is in decline internationally. According to the index compiled annually by the V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg, there are only 29 “liberal democracies” worldwide that meet all the defined criteria. If we add the “electoral democracies,” where elections are held but other important civil rights are restricted, we arrive at a total of 88 countries, home to 28 percent of the world's population: just over one in four of the eight billion people on Earth.

Democracy: now only an exception internationally

Twenty years ago, in 2004, the majority of humanity still lived in democracies: 51 percent, compared to 49 percent in autocracies. Since then, authoritarian forms of government have experienced a strong upswing and continue to gain ground. Ninety-one countries already have autocratic governments, and 45 countries are (further) moving toward autocracy, according to the institute’s assessment—while only 19 countries are currently democratizing. The record election year of 2024 confirmed this trend.

So, what is going wrong?

In many countries, a “rise in populism” is blamed for this development: parties, mostly from the right wing of the political spectrum, that promise simple solutions to complex problems.

The Economist, whose Democracy Index comes to similar conclusions as the V-Dem Institute and counts 25 “full” democracies, sees this as merely a symptom, not the cause: democracy has “not a populism problem, but an efficiency problem.” Of the categories underlying the index, “government functioning” has by far the worst average rating. The Economist sees a “tipping point” being reached, beyond which it will become more difficult to solve the problems.

The state must deliver

And with “government functioning,” we are already on the subject of infrastructure, “one of the most visible forms of government service delivery,” as US economist Francis Fukuyama writes.

Fukuyama, who in 1989, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, was convinced of the ultimate victory of democracy as a form of government and therefore proclaimed the “end of history,” warns today that people judge democratic systems by their results: “When democracies perform poorly in providing public goods such as infrastructure, trust declines and support for authoritarian alternatives grows.”

Some of the world’s most established democracies, such as the US, the UK, and Germany, have failed to deliver on infrastructure, Fukuyama observes, citing as examples the “snail’s pace” at which the California High-Speed Rail project is progressing. Approved by referendum in 2008, the project is still under construction 17 years later: a first section is being built in the Central Valley, but there is still no prospect of it becoming operational; the latest progress report from 2025 does not mention an end date or opening date either.

In the UK, only the planned section to Birmingham remains of the HS2 high-speed project, which was intended to connect London with the cities of Manchester and Leeds in northern England, less than half the original route length; even 13 years after the government gave the green light for the project, there is still no reliable timetable for it, criticizes the British Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee.

In Germany, the “Stuttgart 21” railway station project, first presented to the public in 1994 and under construction since 2010, is still not complete after around 15 years of construction; the opening has just been postponed again, indefinitely. And the once proverbial punctuality of Deutsche Bahn is reaching new lows: last October, almost every second long-distance train (48.5 percent) was delayed.

The social contract is at risk

Such failures jeopardize the “output legitimacy” of the state, says Fukuyama, and thus strain the social contract, the foundation of democracy: Citizens give the government decision-making power over large parts of public life and expect guarantees of security, progress, and prosperity in return—a simple “tit-for-tat mechanism,” as Dutch economist Hans Keman calls it.

Keman has examined the state of governmental legitimacy and support for democracy in 36 European countries. The empirical correlation is clear: states that are perceived as effective achieve higher approval ratings for democratic institutions.

The reverse correlation can also be demonstrated: when governments cut public spending and reduce investment in infrastructure, for example, confidence in the effectiveness of the democratic system declines and people increasingly turn to extreme anti-establishment parties. A study by Sweden’s Riksbank, which evaluated 200 elections in European countries between 1980 and 2015, found that such austerity policies have “significant political costs”: a one percent cut in local public investment leads to an increase in the share of votes for extreme parties of around three percentage points.

A “doom loop” of disappointment and hostility toward democracy

Political fragmentation further restricts the scope for action of those in power, meaning that they are even less able to “deliver” and mistrust of the democratic system continues to grow – the authors of the study refer to this as a “doom loop.”

The good news is that this trend can be reversed. A study by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel) has examined the impact of regional support from EU funds in structurally weak regions. These funds, for example from the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund, are largely used for regional infrastructure projects, such as in the transport sector, whose effects are directly felt by the population. In regions receiving such funding, the IfW study found a decline of two to three percentage points in the share of votes for right-wing populist parties in the European Parliament elections – infrastructure as a democratic stabilizer.

Every euro is doubled

The positive impact of government investment is, of course, also linked to the economic effects of such interventions, such as the creation of additional jobs. Programs such as Germany’s special fund for infrastructure and climate neutrality, which will invest 500 billion euros in the rail network, among other things, over the next ten years, are paying off immediately. The German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) has calculated that economic output will increase by an additional two percent as a result of the investment package – every euro invested will generate two euros in return.

The prerequisite for the effects predicted by the DIW is that the money is used as announced and does not “trickle away,” as the German Transport Forum, Deutsches Verkehrsforum, has already warned. According to its calculations, only one-third of the funds could actually reach the transport infrastructure, while the rest would be misappropriated with the help of budgetary tricks. The Federal Audit Office, Bundesrechnungshof, also warns against this and calls for at least “the criterion of additionality” to be laid down by law for the investments.

When the government fails to deliver on its promises, the “feedback loop” observed by former US Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg comes into play between “public institutions letting people down and people then hesitating to empower those public institutions to solve their problems.”

So, what should be done?

In my view, three things are necessary:

- First, we must invest sufficiently in infrastructure. As we have seen, cutbacks in this area have immediate repercussions and long-lasting effects. That is why the necessary funds must be made available reliably and for the long term—annual uncertainty due to politically determined budget decisions, as in Germany, for example, is not a sustainable model.

- Second, implementation must be ensured. Of course, a democratic system with its participation rights and the requirement to take into account the rights and interests of all stakeholders is inherently slower than an autocracy, where the government can simply make decisions. But for key projects, there must also be ways to ensure rapid implementation in a democracy. Canada recently established a “Major Projects Office” under the Prime Minister to accelerate infrastructure projects that are in the national interest through streamlined procedures. The list of prioritized projects also includes the Alto High-Speed Rail line, which will connect Toronto and Quebec City.

- And third, we need cross-party cooperation. Major infrastructure projects have a longer time horizon than legislative periods. Australia’s largest infrastructure project, Inland Rail, has felt the effects of this. The planned 1,700-kilometer freight railway line was cut to a third of its length after the change of government in 2022, with the larger part initially halted and postponed indefinitely. Such projects require staying power and therefore consensus across party lines.

We are the state

However, in my view, the demand that politicians must “deliver” falls short. Democracy is not a service that we order. Democracy must be shaped by all of us. Because unlike the saying “L’état, c’est moi” – “I am the state,” which is (albeit incorrectly) attributed to the absolutist “Sun King” Louis XIV, in a democracy it is true that “We are the state.”

So, what can we do to resolve the dilemma described above and strengthen democracy?

As a company, we can deliver on our part, in other words, do our job. At Vossloh, this means making our switches, sleepers, and rail fastenings as durable, sustainable, and economical as possible, while also enabling intelligent, predictive maintenance of the entire system. In this way, we increase the availability of the rail infrastructure and reduce the life-cycle costs of the components. That is our promise to our customers – and at the same time our contribution to a functioning infrastructure.

And as a citizen? I can: go out and vote. Give my vote to democratic parties. Participate constructively in the political debate. And also: acknowledge that democracy cannot deliver at the push of a button and that some things take a little more time.However, deliver we must. I am convinced that infrastructure is the most important construction site of our democracy.

Image sources:

Header image: "Democracy" by Marija Zaric, Unsplash

No high-speed in construction: California High-Speed Rail (Courtesy California High-Speed Rail Authority)

Almost every second train is late: Deutsche Bahn (Copyright: Deutsche Bahn AG / Oliver Lang)

Pete Buttigieg: “Public institutions are letting people down.” (United States Department of Transportation)

References and further reading

V‑Dem Democracy Report 2025: „25 Years of Autocratization – Democracy Trumped?“

The report analyzes data on 202 countries and shows that in 2024, for the first time, there are more autocracies than democracies (91 vs. 88). Only 29 countries are considered liberal democracies. The proportion of people living in democracies fell from 51 percent in 2004 to 28 percent in 2024, while 72 percent of the population is ruled autocratically. Nearly 40 percent of people live in states that are currently moving away from democracy.

Economist Intelligence Unit: Democracy Index 2024

The index ranks 167 countries according to five categories. It distinguishes between 25 “full” democracies, 46 “flawed” democracies, 36 hybrid regimes, and 60 authoritarian regimes. According to the index, only 6.6 percent of the world's population lives in a full democracy, while 39.2 percent lives under authoritarian regimes. The index emphasizes that democracy has more of a performance problem than a populism problem; weak governments and inadequate services undermine trust.

Note on the use of democracy indices

The indices cited in the article from the Varieties of Democracy Project (V Dem) and the Economist Intelligence Unit (Democracy Index) are considered established benchmarks for measuring democracy globally. However, they are not free from methodological criticism:

- V‑Dem‑Index: In addition to objectively measurable criteria, the V-Dem Index relies heavily on assessments by a small group of country experts (usually five per country). Critics complain that the selection of these experts and the weighting of the indicators are not transparent and that this can lead to distortions. For example, it is pointed out that some authoritarian states received perfect scores in the objective sub-indices, while democratic countries were downgraded by the subjective sub-indices. In addition, analyses point to contradictions between the various sub-indices and criticize V-Dem for basing its assessments too heavily on “arbitrary expert judgments.”

- Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit): The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index is also based on expert surveys and has been criticized for its strongly liberal concept of democracy. Political scientists complain that the index does not include indicators of social security or economic equality and is based only on a limited group of anonymous experts. Some commentators see a bias in the compilation of indicators and the selection of topics (e.g., the detailed presentation of specific conflicts).

Further reading:

- Indian Century Roundtable: „Inside the V‑Dem Rankings“ – critical analysis of the V-Dem Index and its measurement methods.

- GlobalOrder: „The Inaccuracy of Methodology: The Case of V‑Dem“ – discussion on subjective evaluation methods and expert selection.

- ECPR‑Blog „The Loop“: „Is the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index little more than a joke indicator?“ – overview of the main objections to the Democracy Index, including the lack of social indicators and liberal bias.

- Solidarity Post: „The Democracy Index is biased propaganda“ – critical commentary on ideological premises and thematic selection in the Democracy Index.

These assessments do not affect the fundamental validity of the indices, but they do help to place their results in the context of academic debate.

Cambridge Report „Global Satisfaction with Democracy 2020“

The comprehensive global data project combines 25 surveys with four million responses from 1973 to 2020 and shows that dissatisfaction with democracy has risen sharply since 2005, reaching a record high in 2019. The report provides regional analyses and examines correlations with economic development.

The authors warn that democracies lose credibility when they perform poorly in providing public goods such as infrastructure. Citizens judge governments by their results; autocratic regimes sometimes appear to be more efficient. The authors emphasize that the “social contract” is based on reciprocity and can erode if “output legitimacy” declines.

Keman defines “stateness” as the state's ability to provide legal protection, welfare, and infrastructure. He argues that inadequate or unfair provision of public services undermines the legitimacy of democracy. Historically, social and infrastructure programs have strengthened the relationship between the state and society.

Riksbank Working Paper: „The Political Costs of Austerity“ (2022)

The authors analyze 200 elections in Europe. They find that cuts in public spending that reduce regional GDP by one percent increase the share of votes for far-right and far-left parties. In the baseline projection, austerity leads to a three percentage point increase for such parties four years later. Austerity also reduces voter turnout and increases political fragmentation.

IfW Kiel Policy Brief: „Paying Off Populism“ (2024)

The study shows that investments from the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund in structurally weak regions reduce the share of votes for right-wing populist parties in European elections by two to three percentage points (a reduction of 15–20 percent). At the same time, trust in democratic institutions increases.

DIW aktuell: „Sondervermögen für Infrastruktur: 500-Milliarden-Euro-Investitionspaket würde deutsche Wirtschaft aus der Krise holen“ (2025) (only available in German)

The German Institute for Economic Research calculates that a ten-year investment package of 500 billion euros would increase German economic output by more than two percent annually. The cumulative effect would be twice as high as the expenditure (multiplier ≈ 2).

OECD „ 2024 Global Forum on Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy “

The OECD paper presents building trust as a core task of democratic states. An efficient approval policy, improved regulation, and comprehensive stakeholder participation should facilitate investment in climate-friendly infrastructure. Good infrastructure contributes to citizen satisfaction, promotes participation, and thus supports the legitimacy of democratic systems.

Other sources cited:

- California High-Speed Rail: “Project Update Report 2025”

- Committee of Public Acounts, House of Commons, UK: “HS2: Update following the Northern leg cancellation”, February 2025

- Deutsche Bahn: Stuttgart 21 – Historie

- Deutsche Bahn: Erläuterung Pünktlichkeitswerte für den Oktober 2025 (only available in German)

- New York Times, Interview Pete Buttigieg: „How to regain political trust” (paywall)

- Deutsches Verkehrsforum: „Sondervermögen versickert – Politik-Brief November 2025“ (only available in German)

- Bundesrechnungshof: „Grundbedingungen für ein wirksames Mehr an Infrastruktur“ (only available in German) Major Projects Office Canada: Projects and transformative strategies map